Expanding social media video journalism is a smart move for any marketer. It’s hard to deny the potential for awe-inspiring content that thrills clients and leaves viewers captivated. We’re talking YouTube shorts, flashmobs, crowdsourcing, branded entertainment, conference coverage, Q & A sessions with experts, video segments… the possibilities are endless.

Before scripts are written and shoots booked, consider which camera will be the best fit. We’ll narrow the playing field and compare two main categories of consumer video cameras: a tried-and-true professional grade camcorder or the ubiquitous, cost-effective DSLR.

Before making a snap judgment based on budget, consider the situation in which the camera will be used:

- What hardware is optimum for its intended use?

- Which tool is best for creating stirring, high-quality video?

- How hard you want to work before hitting the record button?

Both pro camcorders and DLSR classes of camera have their merits ” both have their downfalls.

What’s The Difference?

A DSLR (Digital Single Lens Reflex) is a professional grade still camera with interchangeable lenses. As of late, more and more models allow video recording. Because of their still camera roots, the video options are typically tacked on to an item primarily set up for still photography. This means something pivotal like a microphone is an afterthought in a DSLR. The cost? A Canon T5i DSLR can be picked up for only $650+shipping (lenses sold separately).

In contrast, a camcorder is specifically designed to record video. And we’re not talking about the little handycam parents used in the 90s to film elementary school plays. We’re talking about the big behemoths television photographers point at car crashes and burning buildings. These are all-in-one systems. They’re equipped with ports for microphones and smooth-as-butter servo zoom lenses. They’re also typically much larger and heavier than a DSLR. Cost? It’s not uncommon to drop more than $5,500 on one, like the Panasonic AG-HPX225 camcorder.

Find What Fits Your Needs

Think about when, where and why the camera will be used. Keep in mind future lighting situations. Will the camera be used in a studio where you’ll have complete control over your lighting, or will you typically be going off to conferences and conducting interviews on the floor?

Anyone who’s tried to take photos at a conference knows presentation venues are notoriously dark. As mentioned in our previous post, cameras need much more light to see than human eyes do.

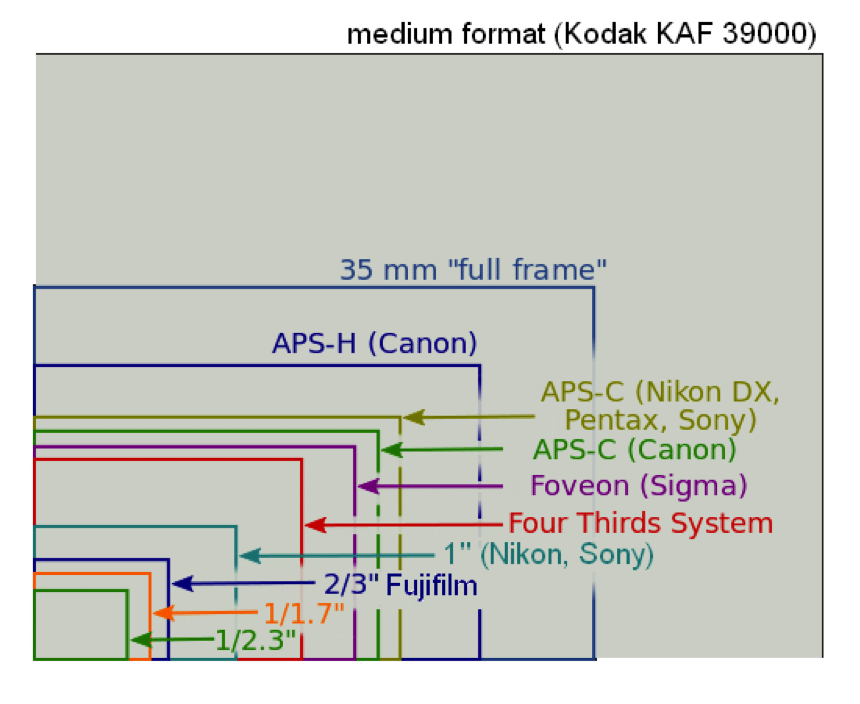

When it comes to quality, the size of the image sensor (the plate inside the camera that captures light) matters the most. Camcorders are at a distinct disadvantage here because they contain much smaller sensors than DSLRs, meaning they can absorb less light, resulting in a much dimmer image. In contrast, DSLRs have much larger sensors that gobble up light, making their image quality superior in those tastefully lit (but horribly dark) conference halls.

This sensor difference ties into the overall look. Any DSLR’s sensor is vastly superior to what is found in a camcorder. For comparison, at AIMCLEAR we have a Sony PXW-Z100 camcorder with a 1/2.3″ sensor and a Canon D70 with an APS-C sensor. This chart from Wikipedia does a great job of highlighting the difference.

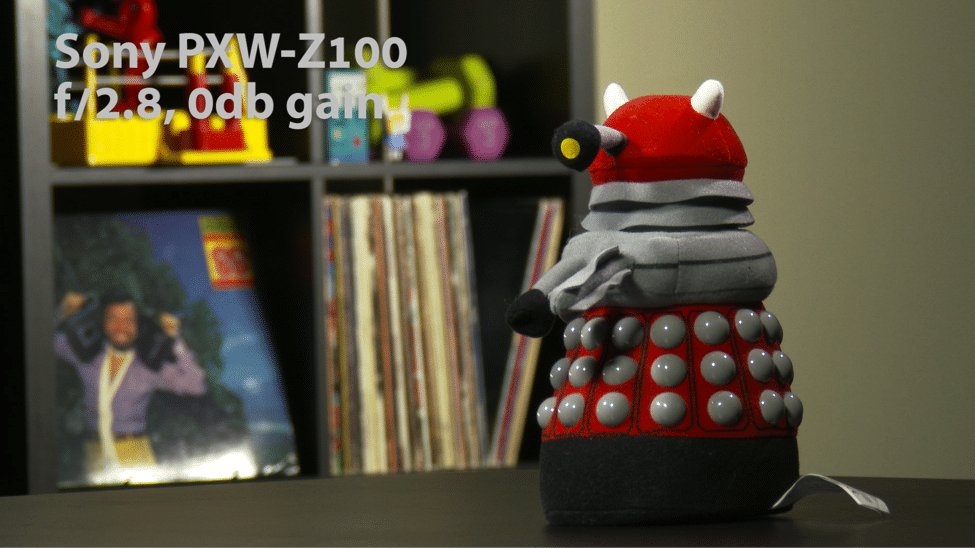

The Sony’s image sensor is puny in comparison to the Canon’s. Check out this side-by-side comparison between the two, both taken at about nine feet back.

The image quality produced by the DSLR blows our camcorder out of the water. See how the DSLR’s background is blurrier and out of focus? We photogs call this shallow depth of field ” it leads to a professional, cinematic look. Pair this with a low aperture lens and the depth can become stunning.

Taking it Easy ” Or Not

DSLRs were designed for still photographers. As such, there are a limited number of dedicated buttons on the camera itself, and most of those buttons are better suited for taking stills. Know this: There is a disadvantage when using a DSLR because of its lack of analog controls, like switches and buttons. You’re going to spend a lot of time trudging through touch-screen menus, hunting for the setting you’re trying to change. In contrast, a camcorder has plenty of big, beautiful buttons all over, giving quick, easy control over the iris, white balance, gain, audio levels, filter selection, etc.

For example, to set the custom white balance on the Canon D70, take a still photo of something white, then go into the main menu, tab three sections in, scroll down to “Custom White Balance,” choose the image and select “OK.” That’s 11 button presses on the D70. On the camcorder, all you have to do is point at something white and hit the white balance button. One button press for the Z100 compared to up to 11 for the D70.

Seeing Clearly: Lenses

A high-quality camcorder lens will cover the gamut in terms of zoom. They allow for extremely wide shots, very tight close-ups and everywhere in-between. Many camcorders come with lenses permanently fixed to the body ” and if you have a model with a detachable lens, get ready to drop a few grand for a new one. Why are they so expensive? It’s all inside. Camcorder lenses have servo zooms, meaning you can adjust how tight your shot is with buttons on the camera, rather than manually zooming like with a DSLR lens. This will make pushes (zooming in) and pulls (zooming out) perfectly smooth.

A DSLR’s key feature is interchangable lenses. Every lens is different and provides a distinct look. They are typically cheaper than camcorder lenses, mainly because they sacrifice the servo zoom feature and are far more specialized. Once you understand the optics of camera lenses (we’ll save that bit of geeking-out for a different post), you’ll end up buying lenses to fit your specific needs. A quick Google search will reveal that a high-quality lens could end up costing more than the camera itself, so choose wisely. Three lenses ” close, medium and wide ” should be able to handle any shoot, and you’ll still end up saving money compared to a camcorder. Plus, you get to bask in the glory of the sexy, sexy depth of field.

Understanding Audio Anatomy

DSLRs’ biggest downfall is their audio hardware and quality. They normally have just one mic input and no headphone jack. This means if you’re going to use an external microphone, there’s no way to hear what it’s picking up. Also, you have very little control over the audio levels or how sensitive the microphone is. For a Canon DSLR, you have to once again navigate through the menu to adjust the mic levels, making it a real pain to use. For quality DSLR sound, buy an external audio recorder like the $200-250 Zoom H4n. This way, audio levels can be monitored with headphones, plus two different microphones can be plugged in at the same time.

Camcorders, on the other hand, have serious audio gear built right in. They have mic inputs on the side of the camera, and many even come with external shotgun mics to replace the low-quality stereo mics built-in, like our Z100. Knobs on the side let you quickly ” and intuitively ” adjust the audio levels, while a headphone jack allows sound monitoring. In terms of audio kit, a camcorder mops the floor with a DSLR.

Finding Your Match

Making this decision lightly or on a whim could be a mistake, because each camera has its own merits and flaws. DSLRs are offer vastly superior image quality, customization and are easier on the wallet. On the other hand, they require buying accessories like audio equipment and microphones before you can use them for video. They also require a great deal of patience to use due to their clunky interfaces and interchangeable lenses. Camcorders provide everything to start filming right out of the box. The wide array of buttons and switches give you complete control over basic functions rather than dealing with those pesky menus, but they fall short in low light situations due to their pitifully small image sensors.

Bottom Line: You get image quality with a DSLR and ease of use with a camcorder. So, which one is best for creating your next video?

(“Sensor sizes overlaid inside 2014” by MarcusGR – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons)